To protect both patients and staff, eye care professionals need to ensure the highest level of infection control is adhered to for medical devices and their environment. By Australian Standards, devices that contact the eye are required to undergo high-level disinfection with a medical device disinfectant found on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG). This is essential as harmful microorganisms can spread in a myriad of ways:

- Inadequate disinfection of ophthalmic equipment

- By contact with contaminated environmental surfaces, or;

- Patient to staff transmission.

Let’s explore some of the most common infections in ophthalmology, the pathogens behind them, and how you can protect your practice with Tristel’s high-level disinfectants.

Common Eye Infections in Ophthalmology

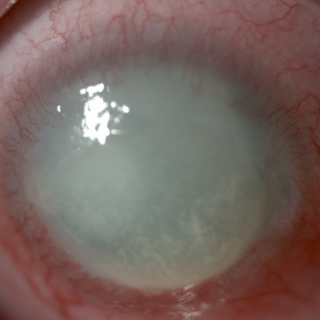

1. Keratitis

Keratitisis an inflammation of the cornea, often caused by bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus, as well as fungi and parasites1.

Symptoms include:

- Moderate to intense pain

- Impaired eyesight

- Corneal ulceration

- Sensitivity to light (photophobia)

- Red eye

2. Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK)

AK is caused by a parasite which feeds off the cornea of the eye, which are ubiquitous within the environment. These parasites are commonly found in:

- Contact lens accessories

- Tap water

- Dust

- Swimming pools

Contact lens wearers are most at risk with studies showing that within the United States approximately 85% of AK infections occur in this group. AK can mimic other infections such as conjunctivitis and herpes simplex virus keratitis, making diagnosis tricky. If left untreated, it can lead to permanent corneal scarring and occasionally blindness³.

3. Adenoviral epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC)

EKC is a highly contagious severe form of conjunctivitis caused by adenovirus. It accounts for approximately 92% of acute epibulbar infections are caused by the adenovirus and is a major concern in hospital environments. Within larger hospitals (>500 beds), for every 1000 treatment cases, 4.7 are estimated to be from EKC.

Major risk factors relating to nosocomial outbreaks of EKC include:

- Inadequately disinfected ocular instrumentation, and:

- Insufficient hand washing between healthcare staff and patients⁴.

Human adenovirus (HAdV) is a hostile pathogen, surviving for long periods outside of the human body on surfaces such as tonometer tips for nine days, and on plastic for up to 35 days.5

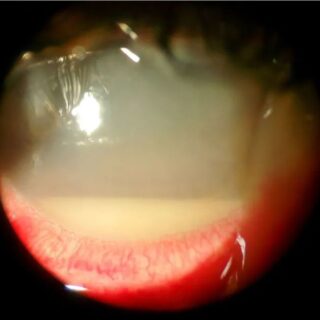

4. Endophthalmitis

Endophthalmitis is an inflammatory condition inside the eye, caused by either bacterial or fungal infection, such as Candida albicans. Where Endogenous (bloodborne/internal cause) endophthalmitis is the less common form of the disease, exogenous endophthalmitis arises through:

- Introduction through trauma or surgery

- Preceding keratitis.

The epidemiological characteristics of patients who contract this infection include:

- Postoperative infection incurred after lens removal or implantation

- Infections post corneal transplant

Other notable infections caused by pathogens of concern in ophthalmology include sty, uveitis, cellulitis, and ocular herpes. Eliminating the initial risk of infection is essential in helping prevent the spread of these pathogens.

Microorganisms Resistance to Disinfectants

Microorganisms vary in their resistance to disinfectants.

How Tristel can help

Tristel has a range of high-level disinfectants with our globally trusted chlorine dioxide (ClO2) chemistry for both medical devices and surfaces.

Why chlorine dioxide?

- Destroys microorganisms as an oxidiser

- Microbes cannot develop resistance to ClO₂

- Fast acting

- Device compatibility

Our Products

References:

1 S. Tuft MChir and M. Burton, “Focus – Microbial keratitis,” London, 2013.

2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Parasites – Acanthamoeba – Granulomatous Amebic Encephalitis (GAE); Keratitis,” 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/ acanthamoeba/index.html (accessed Sep. 01, 2020).

3 All About Vision and C. A. Knobble, “Corneal Ulcer: Causes And Treatment,” 2016. https:// www.allaboutvision.com/conditions/cornealulcer.htm (accessed Sep. 01, 2020).

4 A. Bialasiewicz, “Adenoviral Keratoconjunctivitis,” Sult. Qaboos Univ. Med. J., 2007, [Online]. Available: https:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC3086413/.

5 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “Adenovirus-associated epidemic keratoconjunctivitis outbreaks–four states, 2008-2010.,” MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep., vol. 62, no. 32, pp. 637–51, 2013, [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/pubmed/23945769%0Ahttp:// www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.

6 Rutala, W.A., Peacock, J.E., Gergen, M.F., Sobsey, M.D. and Weber, D.J. (2006). Efficacy of Hospital Germicides against Adenovirus 8, a Common Cause of Epidemic Keratoconjunctivitis in Health Care Facilities. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 50(4), pp.1419–1424. doi:https://doi.org/10.1128/ aac.50.4.1419-1424.2006

7 S. A. Klotz, C. C. Penn, G. J. Negvesky, and S. I. Butrus, “Fungal and Parasitic Infections of the Liver,” Clin. Microbiol. Rev., vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 662–685, 2000.

8 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, 2008; Miscellaneous Inactivating Agents,” CDC website, no. May, pp. 9–13, 2008, doi: 1.

9 V. Thomas, G. McDonnell, S. P. Denyer, and J. Y. Maillard, “Free-living amoebae and their intracellular pathogenic microorganisms: Risks for water quality,” FEMS Microbiol. Rev., vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 231–259, 2010, doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00190.x. 10.

10 Optometry Australia, “Infection Control and COVID-19 factsheet,” 2020. [Online]. Available: http://www.waht. nhs.uk/en-GB/Our-Services1/Departments/InfectionControl/Infection-Control-and-MRSA/. fcgi?artid=PMC4604776.